Introduction

On Friday 19 July 2024, CrowdStrike suffered a serious outage in which over 8.5 million computers were taken offline. Whilst it may have first appeared to be a cyber-attack, it was actually a faulty update to CrowdStrike Falcon which led to computers crashing to a blue screen on boot. Many organisations were affected, and in some cases were unable to access computer systems for multiple hours. This outage saw airports, banks, and financial exchanges affected; leading to one of the largest single IT outages in recent years.

This report aims to explore both the threat actor and business perspectives of this incident; exploring the reactions from both legitimate entities and malicious attackers. Alongside this, the potential lasting impacts and what can be learnt from this incident will be explored.

The threat actor’s perspective

Handala’s Phishing Campaign

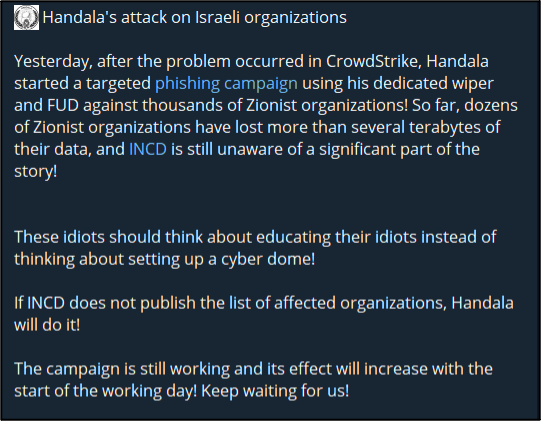

On 21 July 2024, following the initial stages of the CrowdStrike incident, pro-Palestine hacktivist group Handala stated via an English-language cybercriminal forum and its official Telegram channel that it had orchestrated a phishing campaign designed to trick users into downloading the group’s custom-made Hatef wiper. This malware is used to target Windows devices. As with other wipers, it is designed to delete or corrupt all information on infected systems.

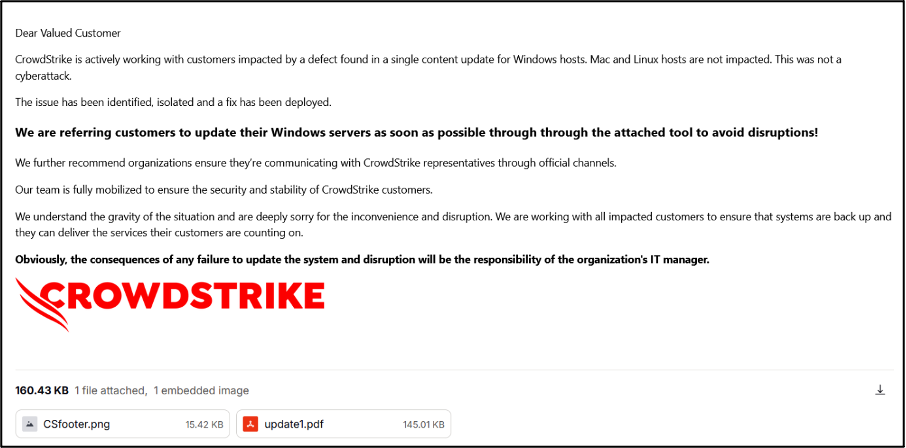

As per its post on a cybercriminal forum, the group’s phishing attack involved sending emails posed as CrowdStrike to inform the victim of known details of the incident. It stated that a fix was rolled out and reinforced that a cyberattack was not the cause. An image of the phish provided by Handala, which is shown in Figure 2, shows two attachments in the email. One is a PNG file titled “CSfooter.png” and the other is a PDF titled “update1.pdf”. Victims are encouraged to update windows servers via the attached tool and open the attachments, though this results in the wiper being downloaded. Using ‘Update’ in the PDF title creates a sense of urgency for the user to open the attachment. The statement contains duplicate uses of the word ‘through’, demonstrating that common spelling errors are found in phishing emails.

Handala claims this campaign was focused on organisations based or linked with Israel, which is the main target for any of its malicious activities due to the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict. The group claims that “dozens of Zionist organizations” have lost terabytes of data due to its activities; however, no proof of this has been shown. Handala appears to be continuing its campaign, stating it “is still working. It also remarks that if the Israel National Cyber Directorate (INCD) does not publish the names of victims then the group will.

Responses from other users was mostly negative, with most not believing Handala’s claims. This is despite the Handala account having a low but positive reputational score on the forum. It is noteworthy that Handala’s data leak site (DLS) has now been flagged for potential phishing.

Microsoft 365 data shared in compound attack

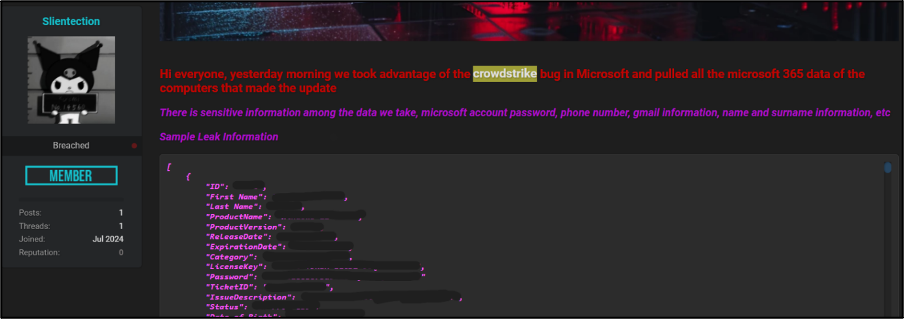

On 21 July 2024, user Silentection uploaded a thread to an English-language cybercriminal forum titled “[2 Million Microsoft 365 Leaks]”. Silentection claimed that “we took advantage of the crowdstrike bug in Microsoft” to steal two million records of user data from systems that had downloaded the update that led to system errors. The data allegedly referred to victim’s Microsoft account passwords, phone numbers, Gmail accounts, full names, and other unspecified information. Silentection provided purported sample images within the post, which is shown in Figure 3. It appears to show the information described by the user, as well as other information such as licence keys, dates of birth, product names, and other email addresses outside of Gmail. Currently the validity of the data is unclear, Silentection appears to be attempting to conduct some form of compound attack or use free advertising from the incident to increase their popularity.

The data has been advertised for $10,000. At time of publication, there is no public indication that the data has been sold. Silentection provided a Telegram channel as a point-of-contact to negotiate the sale of the data. The Telegram account is a public channel and has five subscribers as of late July 2024. The channel information shows “Dark Web Hacking Group” and the details of a private Telegram account operating under the handle kyubey404, also referred to as Kyubey.

The forum profile for Silentection was created in July 2024, with the thread discussed above constituting the only publicly listed one as of the same month. The profile has a zero-reputation score and there is no further information of relevance on the profile page. However, on the thread itself, Silentection has provided a description of the group the account appears to represent, which states “[Slientection Cyber leak and current affairs intelligence apt group]”.

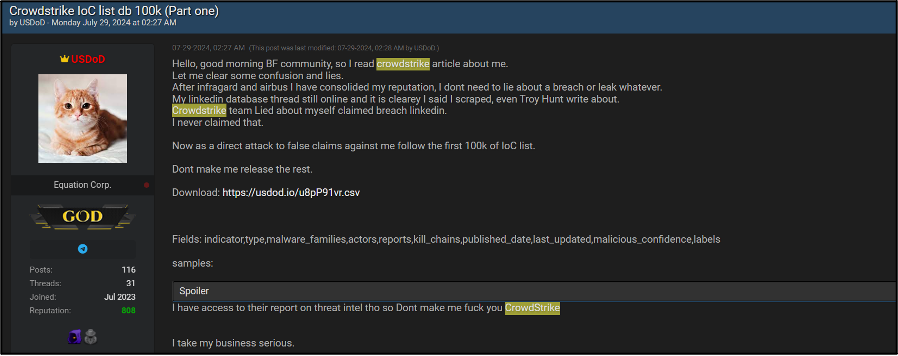

USDoD and CrowdStrike ‘scrapes’

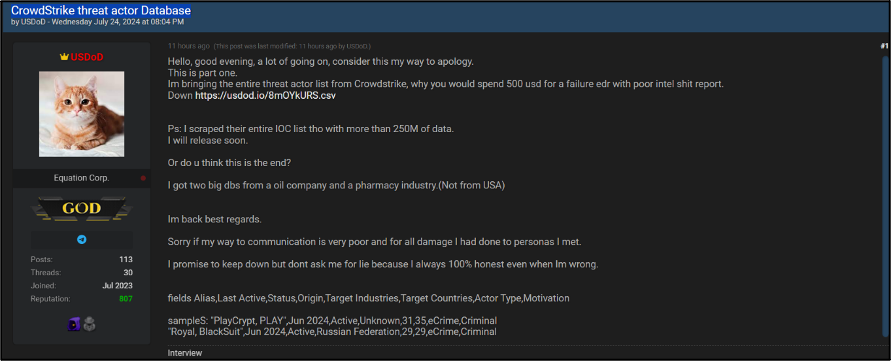

USDoD is a data broker which primarily operates on a well-known English-language cybercriminal forum and claims have breached several large enterprises including the US Environment Protection Agency (EPA), Carglass, and Airbus. In July 2024, the user published several posts on the forum where they claimed to have “scraped” data from CrowdStrike. Whilst the user claims they did this during the incident they state it was a “coincidence” that they scraped the company at the time when the outage occurred. These posts claim to refer to CrowdStrike’s threat actor database, shown in Figure 4, and a list of 100,000 IOCs reported by the company, shown in Figure 5. The latter post was uploaded due to a response from CrowdStrike stating that the claims by USDoD were false. This is despite the threat actor claiming the data stemmed from scrapes rather than a direct breach. USDoD also threatened to release more IOCs should CrowdStrike continue to make false allegations about them. The response from other users has been mixed, with almost all reviews referring to the content of the threads coming from users with no reputation score. The few with reputation were mostly negative about USDoD.

Cybercriminal forum trends

Several trends have been observed across a wide range of cybercriminal forums, despite differences in languages, key criminality, and lifespans of the platforms. For example, cybercriminals appear to be actively mocking the companies involved, particularly Microsoft, by making negative remarks about the company and its software. One user’s message, shown in Figure 6, summed up multiple comments by saying it is “pretty f****d up if you use windows”. Many users were actively promoting the superiority of other operating systems such as Linux, which can be seen in Figure 7.

Many users also commented that CrowdStrike has not or will not receive punishment for the incident, comparing it to the intensive activity by law enforcement against malicious actors. A common conclusion was that the level of damage caused by the CrowdStrike incident was significantly higher than what cybercriminal groups cause. Many users across cybercriminal forums are keen for CrowdStrike, as well as Microsoft, to receive some punishment for the incident, as shown in Figure 8.

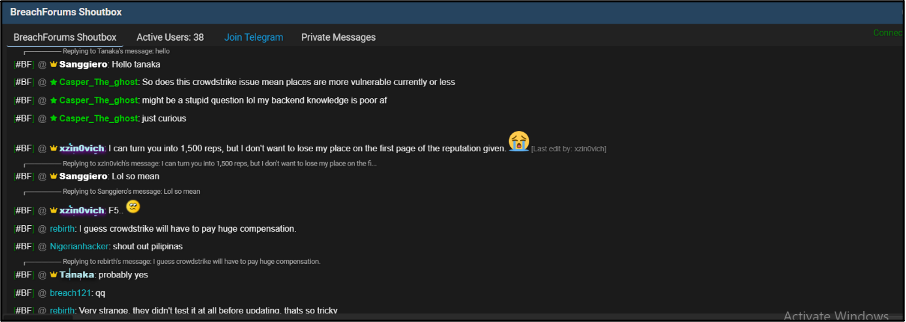

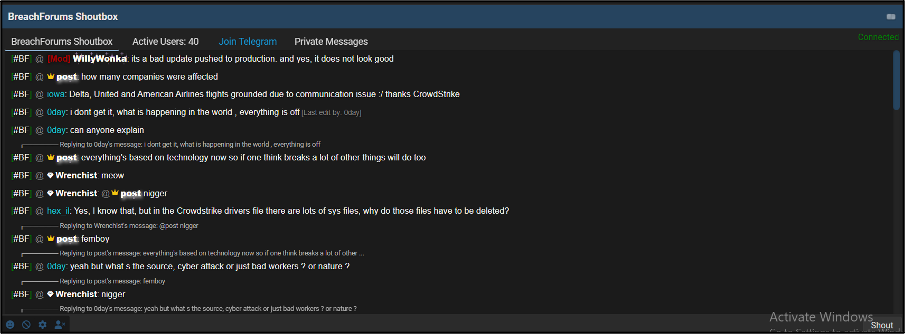

Despite the scale of issues caused by the outage, there was little public discussion around exploiting it for malicious gain. However, several messages were shared in the Shoutbox area of forums, where informal discussion messages are held temporarily. One such message was by user Casper_The_Ghost, who asked “does this CrowdStrike issue mean places are more vulnerable currently or less”. This ultimately garnered no responses, as shown in Figure 9. This highlights a potential lack of knowledge from forum users about the problems behind the initial outage from publicly shared information. Another user also asked, “what’s the source, cyber attack or just bad workers”, which is shown in Figure 10.

Domain-squatting and Fake Help

Away from forums, some threat actors have used the confusion around the issue to conduct malicious actions. For example, a number of phishing emails were sent during the time of the event. Cyjax was able to identify several potentially malicious domains registered around the time of the attack, with some posed as fake help sites and others appearing to display jokes or memes attempting to further mock the issue. Figure 11 shows the domain failstrike[.]com. However, other campaigns do appear to be attempting to spread legitimate malicious payloads as opposed to just negative sentiment. A recent example of this comes from a report from CrowdStrike surrounding fake macro enabled Word documents being shared under the title “New_Recovery_Tool_to_help_with_CrowdStrike_issue_impacting_Windows”. This document delivers the Daolpu information stealer, utilising macros within the document to download the malware.

Other potentially malicious pages were identified, which instead of appearing to deliver malware look to harvest information. This includes crowdstrike-claim[.]com, which is shown in Figure 5. This page is used to ask for several pieces of user information including first and last name, email address, and phone number. This website appears to impersonate Parker Waichman, a US law firm who has a page on its legitimate site regarding lawsuits on the CrowdStrike outage.

It is important to note that many of the impersonated domains found from Cyjax’s research are currently parked and only host domain parking page or lack content. While this does mean that the domain is not sharing malicious content, it is possible for threat actors to activate them after a full campaign is developed. This is a well-established technique and has been previously observed within an Emotet campaign in 2020 to spread malware.

Phishing and social engineering attacks remain a key threat posed by threat actors. This threat has only increased as attackers look to benefit from the confusion caused by the CrowdStrike incident. Building confusion within social engineering campaigns can be a powerful tool, allowing many common red flags to be ignored which may cause an attack to be identified as malicious. Many utilised the need for a widespread fix as a pretext within attacks, only further increasing the legitimacy and success rate of the phish. The number of malicious domains registered hours after the news broke shows how threat actors observe these events closely, utilising them to benefit their own malicious goals.

The business perspective

From a business perspective, the CrowdStrike outage caused two major effects, namely the recovery time objective and maximum tolerable outage. Recovery time objective, or RTO, is the maximum acceptable amount of time for restoring and regaining access to a network after a disruption. The maximum tolerable outage, also known as MTO, is the maximum time a business can be disrupted without significant negative consequences. Incidents such as this may cause an organisation to reassess their risk score with regards to MTO and RTO. It is notable that organisations affected by the CrowdStrike outage had little control to remedy the situation. Many had no way of resuming operations until the third-party CrowdStrike released a fix.

When an organisation works with a third-party to manage its risk, this could typically be seen as a one-way exchange. An organisation shares the risk of managing endpoint detection and response (EDR) with CrowdStrike, in theory lessening the impact of any incidents on the organisation. However, this recent incident demonstrates that there is the two-way exchange when working with a third-party, introducing a pseudo-supply-chain risk into an organisations model. While in a normal situation an organisation can take actionable steps to mitigate an outage, in this scenario they may lose this ability over systems from which they are offloading the risk for.

The CrowdStrike incident is believed to have started at 11pm BST on 18 July, with a fix not being announced until over 12 hours later at midday 19 July. Considering that many organisations affected operated in critical sectors, such as the emergency services in Alaska, the United States, 12 hours is likely far longer than these organisations’ RTO and even possibly its MTO. What those exiting targets may have failed to account for, however, was a situation where there was very little the organisation could do; being almost unable to make partial fixtures or build efficient workarounds to resolve the situation.

This situation may result in an erosion of the trust placed in collaborative security and risk: is there any point to a problem shared if it only results in a potential problem doubled? This then leads back to the original reasoning underpinning collaborating on managing risk. Specifically, organisations do not necessarily want to take on such risk and thus it is beneficial to outsource it to a specialist third-party which can dedicate its time and resourced to the task. The more likely outcome is not that the levels to which organisations utilise third parties will decrease, but rather the level to which trust, and importance of transparency change within the agreement. This may become a rethinking of the analyses needed such that they consider risks out of the organisation’s control. Whilst this has long been an important part of risk management, the CrowdStrike outage served to demonstrate how significant these external risks can be to an organisation.

Conclusions

Overall, both businesses and cyber criminals have taken a unique perspective on the CrowdStrike attack. As explored within this report, both threat actors and businesses reacted quickly to the news of the outage, aiming to maximise the situation for their own goals. For threat actors, this mainly manifested as an opportunity to conduct crime, either benefitting directly from the event via phishing and social engineering attacks; as well as through attempted compound attacks. It is also noteworthy that a significant number of cybercriminals mocked the event. Whilst one might expect cybercriminals to seek every opportunity to conduct crime, many showed morbid curiosities and humour in response. This reaffirms that while threat actors and cybercriminals are commonly observed by how malicious their actions are; behind them are a collective of real individuals, and when analysed as such, it can give a better understanding of their motivations and acts.

This incident required businesses to quickly develop new strategies and work arounds such that they can continue during a comprehensive IT outage. Most interesting is the significance of the wider effects on risk management and risk sharing. As discussed above, many may have originally seen the sharing of risk as a transactional operation, money for a risk handled. Since dealing with this worldwide outage first-hand, many organisations now have experienced how this can be much more of a two-way deal. The specific challenge highlighted within this scenario is the management of risk where control is not necessarily controlled by an organisation. This is something that is beginning to be explored much more widely in vulnerabilities through concepts such as supply-chain risks, understanding the risks that third parties bring when built into one. This event has highlighted how a similar model can be used to analyse risk sharing. Like the traditional supply-chain, an organisation may look to manage this chain, as the level of control to which the organisation has over specific situations is vital. By analysing the potential impact against MTO and RTO, a better understanding of true exposure within the risk models can be built.

As the impact from the CrowdStrike outage settles, both businesses and cybercriminals will look to learn from this event so that their processes can be more efficient. Whether this is to more effectively harness this kind of event for malicious gain, or to ensure that a business has better redundancy plans, the CrowdStrike outage will no doubt have a lasting impact on both cyber in business and in crime.

Receive our latest cyber intelligence insights delivered directly to your inbox

Simply complete the form to subscribe to our newsletter, ensuring you stay informed about the latest cyber intelligence insights and news.