Iran and the USA: an escalation in cyber-warfare?

Last week, Iran's Minister of Communications and Information Technology announced that the country had successfully prevented an attempted "huge cyber attack organised by a foreign state". While he did not provide specific details about the incident, he said that Iran had faced "a highly-organized and state-sponsored attack against the infrastructures of the electronic government and it was identified and repelled by the country's security shield".He did not attribute the alleged attack to a specific country: even if he had, and even if there had been a claim of responsibility, we could not be certain which foreign state was to blame. However, over the last few years, Iran has been engaged in cyber-warfare with several countries, most notably the United States, and various cyber-related incidents have been highlighted in recent months.Back in June, for example, the US blamed Iran for a physical attack on oil tankers in the Gulf of Oman. Amid growing tensions between the two countries, Iran’s secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, Ali Shamkhani, announced that the country's intelligence agencies had discovered and dismantled a CIA-run cyber-espionage network. He stated that several CIA agents were arrested on the basis of intelligence shared with Iran by its allies, and claimed that the Iranian government was building a regional alliance "to counter American espionage".It was reported just a couple of days later that President Trump had authorised the use of cyber-attacks against Iran; the US government apparently felt a conventional military response would result in an unacceptable number of deaths. An attack which took place on 20 June led to Iran losing access to one of its computer databases that had apparently been used in the planning of attacks on oil tankers in the Persian Gulf.Trump’s decision illustrated a change in his current strategy against Iran: the disruption of military systems rather than the risk of casualties in a conventional operation.Cyber-warfare is of course not new, and nor are the debates over its effectiveness. Nevertheless, an attack carried out as part of a military strategy - however successful in targeting and destroying systems - is a short-term response that may even help the enemy because it will alert the adversary to vulnerabilities in its systems which will then be speedily fixed and therefore much more difficult - if not impossible - to exploit again.However, cyber-warfare also encompasses many different forms of attacks, and some offensive cyber operations have had devastating impact. Stuxnet, developed by the US and Israel in 2010, and Shamoon, widely believed to have been deployed by Iran in an attack against Saudi Arabia’s Aramco in 2012, offer two excellent examples.Attribution of attacks, whether carried out for military or cyber-espionage purposes, is also difficult. This is illustrated nicely by a second announcement last week from Tehran’s government, when a minister said that another attack targeting Iranian networks had been foiled. This time, it was claimed the attack was linked to a state-sponsored Chinese hacker group called APT27. Again, no further details were given.Add to this the news that details of approximately 15 million debit cards from Iran's three largest banks were recently posted on Telegram. The leaks from Mellat, Tejarat and Sarmayeh banks began on 27 November but were only acknowledged by the Iranian government on 8 December. Information exposed included account holder names and account numbers; PIN codes associated with them were obscured. While Iran's information and telecommunications minister claimed that the breach stemmed from a "disgruntled contractor who had access to the accounts and had exposed them as part of an extortion attempt", there has also been some speculation that the leaks were in fact the result of a nation-state group looking to foster instability within Iran.Another point worth noting is the burden of proof: for obvious reasons of national security, nation states rarely admit to a serious breach of critical networks; nor do the attackers tend to advertise their actions. In September, for instance, a senior cyber-security official in the Iranian government denied that the country’s oil infrastructure had been successfully compromised by a cyber-attack, despite western media reports to the contrary: two unnamed US officials had told Reuters that Washington had carried out an operation in retaliation for attacks on Saudi Arabian energy facilities.With the economic and political disputes between the US and Iran showing no signs of abating, all organisations operating in the Middle East, particularly those involved in the energy sector, are advised to be on the highest possible alert for cyber-attacks, and to ensure that all systems are up-to-date.

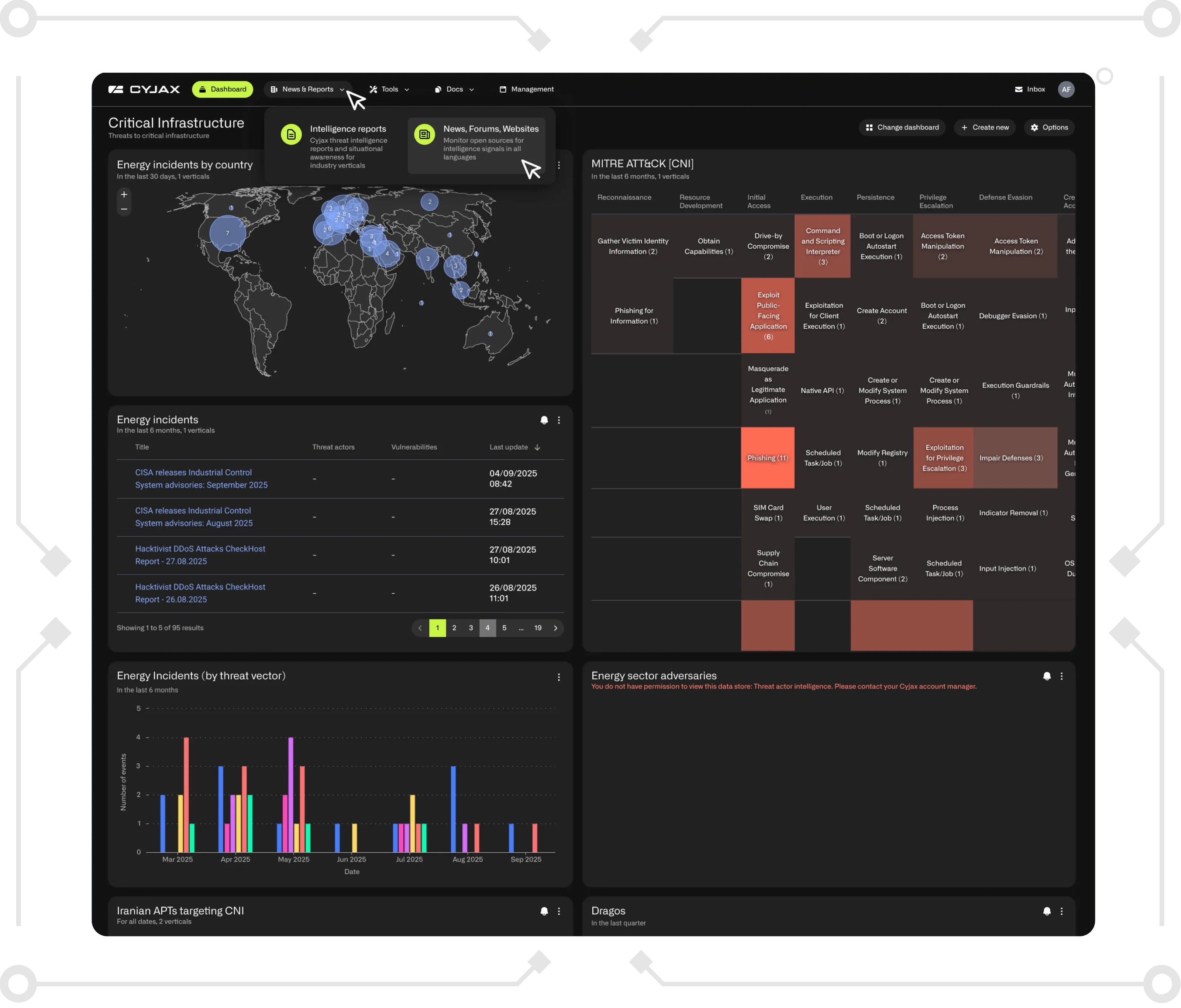

Get Started with CYJAX CTI

Empower Your Team. Strengthen Your Defences.CYJAX gives you the intelligence advantage: clear, validated insights that let your team act fast without being buried in noise.